After the colonial occupation of the Americas, the Brazilian population became formed by the European settlers, the indigenous peoples who already lived in the area and by the slaves brought in from Africa by the settlers. All this has made the ethnic admixture an important factor in Brazil, both socially and culturally. Such phenomena consequentially created a foremost icon in Brazil which is its social stratification.

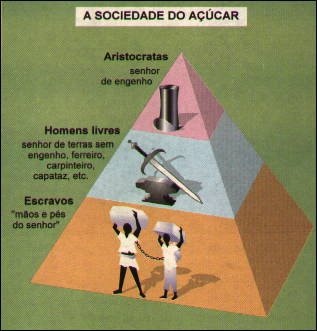

It’s possible to illustrate this in the colonial period, but also very clearly during the sugarcane cycle. At the time Brazil had a small aristocratic class, the lords of the mill and a significant portion of free workers, some of them foremen and captains of the bush, such was their mission to capture runaway slaves, subordinates of the former. Since then it was possible to detect the existence of a middle class, in a superficial way this structure still illustrates well Brazil’s current society.

Brazil has evolved since the colonial period until today, by its political independence, the abolition of slavery, the proclamation of the republic, industrialization and urbanization. This process altered the habits of Brazilian society, but not its basic structure.

The role of the middle class remains serving and imitating the habits of the classes that detain power. It is true to say that, even though this class predominates in salary workers, they have the highest demands for public services, primarily in education and health. Currently there is the phenomenon of the new middle class, the old class “C” which has had significant affluence in recent years.

This conventional middle class, in spite of not being directly connected to the economic power, has significant sway over political decision. In Brazil’s recent history we find various examples of this.

To begin with, the military coup of 1964 had the fundamental support of the middle class. As was in Chile and Argentina, Brazil on behalf of President Joao Goulart intended to implement reforms to alleviate the historic social distortions. The middle class went to the streets in protest against the “subversion” of the order and of values, shielded with religious arguments, but deep down afraid of losing their place to the rising lower class, in the same way that is now occurring in 2011.

While the militants brought some prosperity to Brazil, the vast majority of this class was complicit with the regime and took advantage of getting by with a few trades, enjoying the spoils of patronage practiced at the time. How many from this segment didn’t take advantage of the lack of state regulation to install themselves into public organs without any academic recommendations? The middle class came to oppose the military regime after the depletion of its economic model.

The dictatorship kept most of the middle class drunk with the economic miracle, caused by crunched wage policies of the lower class and by communication created or incentivized by the regime, like the April group through Vista Magazine, Rede Globo TV and the newspaper Folha de Sao Paulo. In the early 80’s the Brazilian population began to feel unemployment and the loss of purchasing power under their skin. All this motivated the middle class to trigger the movement Diretas-Já, which represented the coup de grace for the military.

At a later period, the middle class maneuvered in a way totally manipulated by the media, to elect and jubilate Collor. After the election of Collor the political show descended into the circus and inflation reached 2.000% per year, which again affected the middle class’ consumption, which motivated them to paint their face and knock Collor out of power.

With the impeachment of Collor and the arrival of Itamar Franco, Brazil faced the challenge to control inflation. Itamar appointed a senator, who was his deputy, Fernando Henrique Cardoso as Minister of Finances to implement the Plano Real. The plan served as a stopgap measure for the economy, but any conscious person would know that some of the adopted measures, such as fixed exchange rates, could bring catastrophic consequences, like what occurred in Argentina in 2001.

The middle class had their honeymoon with FHC in his first presidency. With the Real at high value, this social class thought they could live like Europeans and Americans, go on vacation to Disneyland and buy imported cars, something that they had never had. Meanwhile, unemployment and poverty grew, even as it was camouflaged with the complicity of the media. So in 1998, FHC was elected with ease in the first round. However, right away in the first year of the 2nd presidency the middle class’ carriage turned into a pumpkin, the exchange rate became unsustainable and Brazil ended up in the hands of the IMF. With a model similar to that of Argentina went into a grave economic crisis a few years later.

The political frustrations of the middle class were widely exposed in the past eight years of Lula’s government, but without power to influence the higher levels and interfere in the elections. When you visit social networks or debates held on the internet you realize that the central wound of this phenomena is the policies that inserted more than 30 million people into the market of durable consumer goods, which led Lula to gain a 87% approval, the largest ever recorded in the history of Brasil, as was for the election of Dilma as well.

For the middle class, social misery and inequality are a natural difference like day and night. I remember Karl Marx would say that “In this regard, it is irrelevant the fact that you are dealing with the needs of the stomach or of fantasy” The middle class is indifferent to the fact that the people who have always lived under the line of poverty are working, eating and living better, on the contrary they complain about the wages of laborers, household workers, stonemasons and firemen. Often you see people of this class complain that they pay too many taxes, but never stop to think how much the government spends to maintain a member of his family in a university college for free.

Eight years ago a housecleaner’s pay for one day’s service in Belo Horizonte was US$ 4.00, and US$ 30.00 per month in the interior of Minas Gerais, and not having to look far either. One of the most common attitudes is to criticize the welfare Bolsa Familia program, claiming that nowadays you can’t find labor anymore. While the first world is deep in recession, Brazil and its partners in South America are in full employment, and our middle class pretends to not notice that it is being benefitted by this prosperity.

All the while this social class is able to enroll their children in private schools, to pay a private health plan and acquire a brand new automobile. They don’t move a finger to promote a school, public health or a public transportation of quality. For a member of the middle class, these public services are considered class “C”. In their imagination, this segregation is important, this economic, social and racial apartheid, which shows that the current social system is not much different than that of colonial Brazil.

Related Articles