I am in Liberty Square, the liberty to travel over oceans and unknown lands. Those who took a ride on the Cultural Wagon, which “brings the universe of Fernando Sabino to you,” can continue their journey through the literature of Minas Gerais, and the government of Minas Gerais has now ordered that the train be put on track. The driver starts the engine. Attentive ears can hear the whistle blow on the curve.

Today, the public’s attention is drawn to a gigantic ancestral urn, an object of millennial Chinese tradition. The creator is Chinese artist Zhang Huan, the holder of an utterly surreal language. It is one of the four pieces that compose the BH-Asia exposition.

The square itself is crowded with hikers and curious customers. My steps meander into the seventh inner circuit where I read on the glass plate beside the gigantic sculpture: “(…) In China, there is an age old tradition of creating urns into which a person’s personal items are deposited at their time of passing. These goods are buried with the body so that they may accompany the owner who held them so dear on his or her last journey. We invite you to visit the urn consisting of 185 plates of iron ore—the greatest wealth of the Belo Horizonte subsoil —and a floor made of lighted glass planes.”

I watch, observe, contemplate. I almost go into meditation and ecstasy. I turn around and stop in front of the entrance door above a two-step stairway. Do I go in? Do I not go in? A father helps his daughter up the steps; balances the little girl up to the door with his two index fingers. And she stands there looking. Just looking, from outside. The girl enters alone on a journey into the unknown. So peaceful, as if she were going into her playhouse. With empty hands. Without taking any objects dear to her. What sentimental objects would a child take into her urn? A pacifier? A little pillow? Rattles? Bells? A ball? A doll? Her basket? Or the sunlight that slips through the open blinds and bounces off the yellow ribbon in her crib? I imagine my babies, who departed just at the break of dawn on this last trip. What sentimental objects would they have taken, had they been born in China? In Brazil, we don’t have this tradition. I only deposited kisses, forget-me-nots, pansies, lilies and roses harvested in my garden. In the garden we cultivate with all the affection in the world and zeal to attract butterflies and birds, filling a void with the life we dreamed up for them.

The child explores the space, and then comes back around looking kind of disappointed. There was only light. A bright light. The father, down here, extends his arms out and picks up the little girl off the top step; pressing her against his chest. No words. He flies off with her far from Asia, far from the other side as if fleeing from the angel that comes to guide the children on their parting to heaven.

A slender brunette girl with long straight black hair; mouth drawn with liner and red lipstick, floating red dress, one shoulder band, high heel slip-ons, buttoned at the ankle, is accompanied by a young man in jeans and black shirt with a thick silver chain, ear piercing. They snap photos with their mobile phones, photographing the urn and the information board beside it. No one reads what is written. Another young couple joins them. Apparently, they are art students. They seem to have the same interests and goals: a class project maybe. I don’t know. I hope they enter, to catch a ride with my fellow travelers, and know more about the statuesque youths—their art, their worlds, their fears and secrets. And know their sentimental items.

They look at the urn, turn and exchange ganders, make some comment in deep voice and enigmatic smiles. Then they stand silent. Each with their own secret thoughts. Suddenly, the girl of sculptural form and her floating red dress pulls at the guy in the black shirt and drags him off. With her sleek steps like a model on the catwalk, they move quickly far away from Asia, far from China, far from the other side and hang off to hold each other in Liberty Square.

I look back, look to the sides to see if I might find a travel companion. Only passerbyers. I take a deep breath. After seeing the child soul that just came out, I embark on the journey that I will have to make alone. I take the little ox cart that my father made for me when I started studying folklore. It was his last work, at the age of eighty-four years old, as his way of closing a cycle. The first he made was his very first toy. He once told me, “I got my first toy when I was eight years old: an ox cart that I made myself. Took some fig tree branches, made the little wheels, made the deck, fastened on three corn cob bulls, then played and played. Then I just left it out there. The wagons drove up with their carloads of corn. The cars drive right smack against the wall. I closed my eyes to not see them run right over mine. Ze Paulo jumped down from the reigns, halted the bulls and pushed my little car aside. I was obliged to him for the rest of my life. I think that was mostly why I liked him.”

The urn, gigantic. It has room for all my sentimental objects: my Notebook of Lost Time where the hiatus between elementary school and high school, I copied poems, quotes and thoughts of poets and universal thinkers: “I’m looking for space / for the design of life.” ( Cecilia Meireles ) “God! O God! Where are You that You do not answer?” (Castro Alves) “Why your distance / For my company / have you not lowered that star? / Why so high up, Luzia? ( Manuel Bandeira ). “The river reaches its goals because it has learned to overcome obstacles” (Lao Tzu) “One day you learn that no matter how many pieces your heart was has broken into, the world does not stop for you to fix it.” (William Shakespeare) “Imagination is more important than knowledge.” (Albert Einstein).

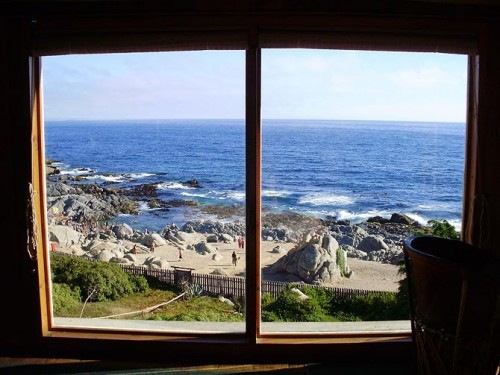

My diary – trustworthy companion of many long nights of abandonment and loneliness – a boat in the crossing the sleepless nights, of celibacy and cloister; all my love letters – boat, windscreen, balm and caresses adrift at sea; the rosebud red pin, a present of my history professor, my graduation godfather, my three bedside books: Terre des Hommes, by Saint Exupery: “What saves us is taking a step. Then another step. It is always the same step, but you have to take it.” The Prophet, by Kalil Gibran: “even as love crowns us, so shall it crucify us (…) And think not you can direct the course of love, for love, if it finds you worthy, directs your course.” Seasons of Absence, by poet Paschoal Motta: “With the petal of thy name, / the morning rose is born;” the little chair that Edimur, my older brother made for my doll. My brother was the most learned and courageous boy in the world. Only he knew how to use father’s tools, ride a balloon tire bicycle while balancing me standing up on the handle bars; how make canoes out of pita and sailing along the weir with me on the bow as Iara, Mother of the waters; the three paper boats, Santa Maria, Pinta and Nina, with which I played with the torrents and cascades and sailed with Edmund, my younger brother, whom I called Mundinho. Mundinho was the one who initiated me into the great voyages – who made my first boat and taught me how to sail, how to deal with storms, monsters and dragons.

With my brother in command, I sailed in search of unknown lands. And dropped anchor in Porto Seguro, with Misses Inez, my mother, screaming out the window: “Get out of the rain boys!” I learned to love my country, this land that “When you plant, everything grows.” I learned a taste for the adventure of living.

Later on, alone in streams, rivers and uncharted oceans, I voyaged across Cape of Storms, facing monsters and dragons. Then I rounded Cape Good Hope.

And even though abandoned by the crew, sailing on a river of tears, on stormy nights, without compass and no lighthouse in sight, with all the stars turned out, I did not let the boat sink nor lose the navigator’s dream. I went on singing the song of the Argonauts, We need not live, we live to navigate.

Related Articles

Comments