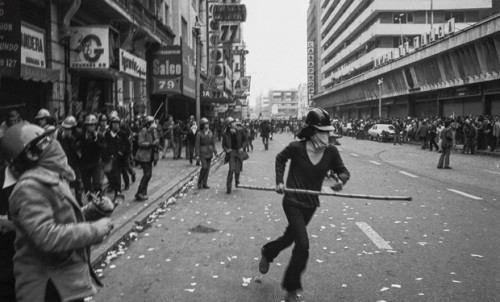

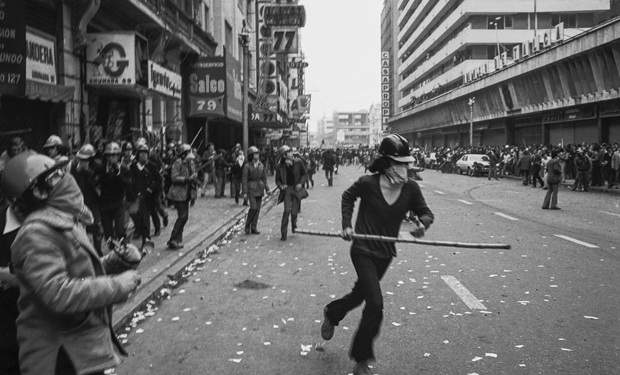

9/11/2013 – Chile, 40 years after the military coup – part I

To the editors,

As forty years have passed since the military coup in Chile, I send this news article that was published by La Tercera, Santiago de Chile, which I translated. The article is extensive, so I am sending it in parts.

Raul Sanchez

Part I – The Twenty-Two Days that Shook Chile

By A. Cavallo, M. Délano, B. Fuentes y K. Trajtemberg. – 08/09/2013 – 03:53

The El Semanal weekly news group takes a look back at the instigators and facts prior to September 11th, 1973, which culminated in the coup d’etat.

The importance that historian Paul E. Sigmund attaches to the period in Chilean history that began in the third week of August and ended on September 11th, 1973, is certainly due to his academic astuteness as well as his witness point of view and experience during the dramatic episode as it developed. Sigmund followed the events that shook Chile day after day so closely that he was able to publish his first analyses about the state coup in the 1974 edition of Foreign Affairs. The provisional conclusion of that article was: “Allende’s policies (…), which mixed high inflation rates with a well-defined polarization of social classes was a recipe for disaster.” Later, Sigmund would explore in greater detail the political vertigo of those twenty-two days as well as the role the United States played in it.

Most Chileans from that time in history experienced this period as Sigmund described it: like a process of historical acceleration, fueled by private tensions and public incidents, and the general sensation that everything would end in violence, a state coup or a civil war. Every one of the survivors from those days—including the main political leaders—point to the last three weeks of Salvador Allende’s rein as a march down tragedy avenue.

There had already been major paralyzing production setbacks. Inflation and the emission of unbacked currency went unbridled. The streets were a stage for common outbursts and a military regiment had been called forth, the Blindados n° 2, which on the 29th of June surrounded the Palácio de La Moneda in an attempt to overthrow the government. This severe incident was seen by some as a “test drive,” by others as a victory for the government while others still saw an “opportunity” to take a decisive turn in the correlation of forces. Looking from these different points of view in order to analyze the same phenomenon, it is clearly revealed how they were tinged by certain ideologies in regards to the interpretative capacities of the country’s actual situation.

The question still hanging in the air after forty years is: why didn’t anyone do anything effective to prevent the disaster? Or was it just inevitable at that point? Every, or almost every, protagonist would claim that on many occasions, since the election of Salvador Allende in 1970, every effort was made to prevent the downfall of democracy while considering the terms already laid on the table. But from the 20th of August 1973 onward, these attempts turned out to be simply drowning arm thrashes.

What really happened during those days? This paper focuses on that period, which until now has not been explicitly analyzed, and touches on a response from the author’s six month long journalistic investigation, based on interviews of the instigators and eye witnesses, including a review of the extensive bibliography available on the subject.

Empirical evidence shows beyond reasonable doubt that in 1973 Chilean society was literally split in two. The parliamentary elections in March of that year put the consistent majority in opposition, composed of the center-right wing, while at the same time advances by the Unidade Popular political party were recorded, which in the end were too slow going for the government to achieve the majority vote before the final mandate in 1976. For a country subject to such high tensions provoked by the majority, it was the worst possible result, a result that would resolve nothing.

This division reflected a fundamental societal disagreement due to the lack of development strategy and political order subsequent to the 1930’s crisis, which may not have been sufficiently deliberated on, or may have been overly exaggerated by the conflicting sides.

However, there was another, perhaps even more profound and dramatic divergence at the time which affected every relevant social and political player: internal dissensions which, at different levels, made people believe that everyone’s survival was in jeopardy. Thus it is true that the government parties were deeply divided—and in some instances in confrontation. It is also true that the military was not completely unified, neither were the right wing and Christian Democrats, or even the Catholic Church, labor and student movements.

Most of these differences did not rise to the surface during the Unidade Popular, neither can they be attributed to this period. Some date back to the early history of these groups, and others attributed to the ideological turmoil that began in the 60’s. But of course there are also cases that incubated or were aggravated with the arrival of the Unidade Popular, UP into the Chilean government. But taken into account as a whole, they confirm what is evident in all political processes of this nature: no group alone could ever provoke a denouement of this magnitude. If at one point in time there was a collapse, it was due to a more or less disgraceful convergence of causes: a multiple organ failure, using a clinical metaphor if you will.

(To be continued…)

Related Articles