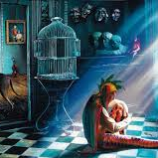

If the assemblage point does not become stationary, there is no way that we can perceive coherently. We would experience then a kaleidoscope of disassociated images. This is the reason the old sorcerers put as much emphasis on dreaming as they did on stalking. One art cannot exist without the other, especially for the kinds of activities in which the old sorcerers were involved.

The old sorcerers called them the intricacies of the second attention or the grand adventure of the unknown. These activities stem from the displacements of the assemblage point. Not only had the old sorcerers learned to displace their assemblage points to thousands of positions on the surface or on the inside of their energy masses but they had also learned to fixate their assemblage points on those positions, and thus retain their cohesiveness, indefinitely.

The clearer the view of our dreams, the greater our cohesion. The cohesiveness of the old sorcerers was such that it allowed them to become perceptually and physically everything the specific position of their assemblage points dictated. They could transform themselves into anything for which they had a specific inventory. An inventory is all the details of perception involved in becoming, for example, a jaguar, a bird, an insect, et cetera, et cetera.

The old sorcerers had superb fluidity. All they needed was the slightest shift of their assemblage points, the slightest perceptual cue from their dreaming, and they would instantaneously stalk their perception, rearrange their cohesiveness to fit their new state of awareness, and be an animal, another person, a bird, or anything.

The mentally ill imagine a personal reality because they have no preconceived objective. They bring chaos within chaos. Sorcerers bring order to the chaos. Their preconceived, transcendental purpose is to free their perception. Sorcerers don’t make up the world they are perceiving; they perceive energy directly, and then they discover that what they are perceiving is an unknown new world, which can swallow them whole, because it is as real as anything we know to be real.

Seeing children’s assemblage points constantly fluttering, as if moved by tremors, changing their place with ease, the old sorcerers came to the conclusion that the assemblage points habitual location is not innate but brought about by habituation. Seeing also that only in adults is it fixed on one spot, they surmised that the specific location of the assemblage point fosters a specific way of perceiving. Through usage, this specific way of perceiving becomes a system of interpreting sensory data.

Since we are drafted into that system by being born into it, from the moment of our birth we imperatively strive to adjust our perceiving to conform to the demands of this system, a system that rules us for life. Consequently, the old sorcerers were thoroughly right in believing that the act of countermanding it and perceiving energy directly is what transforms a person into a sorcerer.

The greatest accomplishment of our human upbringing is to lock our assemblage point on its habitual position. For, once it is immobilized there, our perception can be coached and guided to interpret what we perceive. In other words, we can then be guided to perceive more in terms of our system than in terms of our senses. Human perception is universally homogeneous, because the assemblage points of the whole human race are fixed on the same spot.

Sorcerers prove all this to themselves when they see that at the moment the assemblage point is displaced beyond a certain threshold, and new universal filaments of energy begin to be perceived, there is no sense to what we perceive.

The immediate cause is that new sensory data has rendered our system inoperative; it can no longer be used to interpret what we are perceiving. Perceiving without our system is, of course, chaotic. But strangely enough, when we think we have truly lost our bearings, our old system rallies; it comes to our rescue and transforms our new incomprehensible perception into a thoroughly comprehensible new world.

Related Articles